This hi-tech vandalism is weird enough, but the group planned to actually make the film based on the concepts. The one thing that the guys, who already spent €2.66 million on the whole enterprise, failed to grasp was that all rights for the Dune screen adaptation belong to Legendary Entertainment.

But why do people have this kind of misconception?

It’s been almost a decade since non-fungible tokens (NFTs) appeared and became publicly known. But many people are still confused about how the whole thing works and what is it for? On the fundamental level, NFTs make it possible to bring classical economic concepts such as supply, demand, and private property to the Internet.

The problem comes from the lack of mutual agreement in views on it: some people see it as a scam, while others think of it as a magic pill that will end copyright infringement for good. Actually, both of them are not quite right.

First of all, let’s figure out what all the fuss is about. NFTs are one-of-a-kind digital tokens that exist on a blockchain and are linked to physical or, usually, digital assets. The fact that they are blockchain-based helps add a lot of credibility to it, as it prevents tampering with it and thus makes most of the operations with it trustworthy.

The “non-fungible” part of the name implies that the tokens have no fractional value and are not interchangeable. This already makes them different from any currency, blockchain-based or regular, as NFTs are unique and individualized items, each with its own value.

Reasons for the gold rush around the NFTs

The uniqueness of the tokens is further supported by the process of their production, called “minting.”

To complete this process, the tokens must be digitally signed. It works exactly like the regular signature on a painting and serves to link the creator to the NFT. And when the process is over, boom, the token is tied to virtually anything: a specific hat, a website, a video with cute cats, you name it.

The tokens are issued in limited edition runs, rarely more than a few thousand, which creates an effect of scarcity. But the catch is that NFTs are not “actual” artworks coded into a blockchain, since storing even a 64x64 JPG image in it would be exorbitantly expensive, but URLs linked to the artwork.

Theoretically, an NFTs “TokenID” would make it possible for individuals or corporations to exchange classified information safely as NFTs serve as an artist’s signature combined with a good old “großbuch” with property and transaction records.

Naturally, NFTs, same as actual pieces of art are tradable, but the formation of price is also pretty vague, which is, again, the same as with real pieces of art.

Also, mind that when a certain token becomes hyped and people start trading it, the original emitter gets a royalty percent from every transaction happening between two addresses at any point in time.

Copyright and NFT

Thus here comes another copyright-related issue: NFTs, while being unique and not fractional, do not provide you with any legal ownership on the piece of art you buy and do not prevent copying, alteration, or any other action regarding the artwork in question.

To put it simply: a token is just a piece of hash with transaction data and a URL leading to the thing you’ve bought. Yes, an NFT can’t be copied while maintaining the same value, but they still only represent an asset while not being it.

So you do own a unique hash on the blockchain with a record saying that you have bought it as well as a hyperlink to the file with the piece of art. But this does not equate to the ownership of the artwork itself.

Situations like this may potentially lead to real pieces of art being tokenized and later destroyed for the sake of uniqueness and greed.

And since many people tend to confuse the ownership over a digital transaction code with ownership over a product itself, there is much space for fraud, theft, and copyright infringement. But the variety of items for which one can create a non-fungible token only adds more confusion. This happens because different jurisdictions define “works” in various ways.

A state may consider performances, recordings, and other related works protected by copyright laws equally with the origins, whether it is a literary source or an artistic work of art.

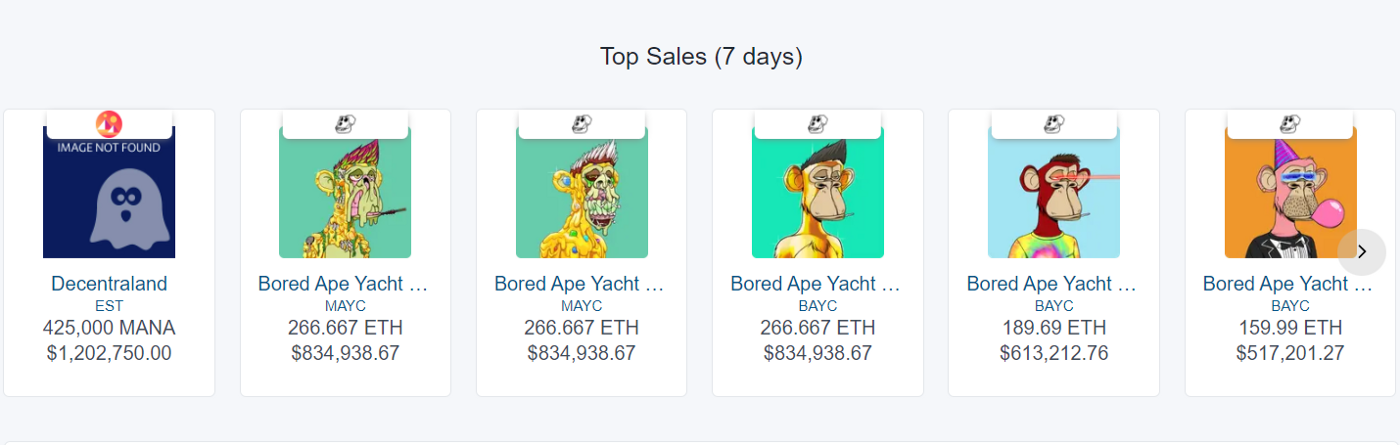

Whopping sums in the NFT market

This means that all rights belong to the original creator of artwork and unless an agreement between the artist and the buyer is made, it will stay the same. So the buyer of an NFT simply gets a unique copy of a product with its author’s signature. This probably explains the whopping $2.5 million one had to pay for Jack Dorsey’s first tweet from 2006 when Twitter just got started. This is not a unique case, though. According to the NFT market overview, there is almost $553 billion worth of tokenized memes and other works of art sold by now.

It might not sound this bad, as even 30 to 50 years ago, artists used to sell their CDs or vinyl to the most loyal fans that were ready to pay anything for a piece directly from their beloved creator. NFTs do the same, but on a larger scale and you don’t even get a limited-edition CD.

And here goes the speculative nature of all collectibles.

Some of them may easily be seen as a future investment. So do consider buying an NFT gif with a meme if you happen to have a spare $560 000. That was the story with an early 2010s Nyan-cat meme; imagine how much a gif with a new meme would cost.

The issue gets even trickier when considering the potential for fraud, which may happen already in the process of minting, when, for example, a minter lies about his or her identity.

This results in artists discovering their work being sold as NFT when they have nothing to do with it. And many of them discovered that NFTs with their works are sold without their consent only months and even years later when suddenly stumbling upon it in an auction.

The problem arises because there is no centralized, regulatory, or legal framework in the NFT market. Basically, anyone can mint anything, whether it is a picture, a tweet, a gif image, or a CAD file, while not being the actual author of it. And people would still buy it, whether due to sentimental reasons or because of viewing it as a financial investment. And if the transaction is verified by the original seller\creator, it is fine.

Potential for the development of NFTs

For now, the lack of international compliance prevents NFTs from being considered equal to traditional copyright ownership. An open and understandable regulatory framework would minimize the possibility of fraud, allowing exchanging copyright within the blockchain itself.

But when and if international compliance is achieved, the huge potential of the NFT will truly unveil.

This may be achieved in the same way as the regular money was agreed upon as a more convenient alternative to barter relations: only with centralized regulation and ways to combat counterfeit the technology may be used as a trustworthy way of transferring copyright.

To sum it up: NFTs are a truly inspiring technology with huge potential that may help improve information and copyright exchange between people all over the world. But as of today, there is not enough regulation and international compliance regarding copyright protection in this new form of a commercial relationship. Also, there is no clear and understandable way to justify an item’s price. This, in turn, makes the technology a desired tool for speculators, making money on hyped pictures. Also you can try our product BORIS for Fusion 360 to empower your 3D designs protection.